Written by Jonah Udall; Select sections of article written by and article reviewed by Dr. Bojana Jankovic Weatherly.

If you or someone you love has an autoimmune disease, you know that these are some of the most challenging chronic conditions to live with. As many as one in ten people have an autoimmune disease in the US, and prevalence is rising rapidly around the world.1 Uncontrolled, these conditions precipitate a gradual deterioration of organ function. Pharmaceutical treatments can slow the process and have life-changing benefits, but they do not stop the disease at its root, and can have dangerous unintended effects.2

Conventional medicine is quick to say that autoimmunity is incurable, focusing primarily on disease management. While managing the disease course and symptoms are key components of treatment (e.g., DMARD medications in rheumatoid arthritis), it is also paramount that we identify and address the root causes and triggers of autoimmunity. Functional medicine has shown that if we can address the root causes and triggers of autoimmunity, it is possible to affect the mechanisms leading to it. Recent research has shed light on the confluence of factors that likely underlie the autoimmune process, and supports a role for natural therapeutics in root cause healing. As we’ve often explored in this blog, much comes back to the gut.

The gut-immune link

Autoimmunity happens when the adaptive immune system, a specialized immune process that specifically targets foreign invaders, gets confused and attacks your own tissues. The contribution of genetics to autoimmunity is well understood, certain genes make our adaptive immunity more likely to get confused in particular ways, leading to particular diseases. But genetics alone are not enough. Two additional factors come together to create the “perfect storm”: environmental triggers and a leaky gut.

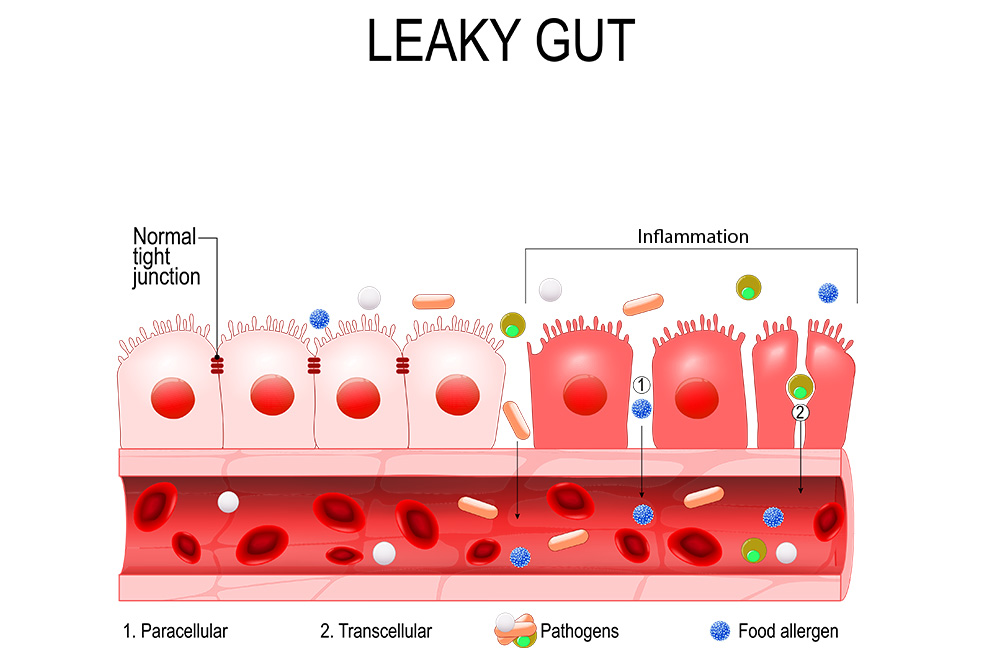

The intestinal lining – a thin, one cell-thick barrier 15 times the size of your skin – is our most important interface with the outside world, housing 70% of our immune system. This barrier has to strike a delicate balance, allowing fully-digested nutrients in while keeping larger molecules and microorganisms out. If this selectivity is compromised, the immune system gets flooded with unwanted materials and can become dysregulated.3

There are several ways intestinal barrier dysfunction can lead to autoimmunity. On one hand, some foreign molecules resemble normal parts of our cells, and a genetically-susceptible immune system may mistakenly attack both when mounting a response against the invader.4 This is called “molecular mimicry.” A leaky gut allows these foreign molecules to encounter the immune system, and fuels the immune dysregulation that leads to an overblown response.

On the other hand, intestinal barrier dysfunction leads to generalized immune hyperreactivity and inflammation. Under normal conditions, harmless substances, foreign and native, are met with an anti-inflammatory tolerance response, but a leaky gut can cause a loss of tolerance that can lead to autoimmunity.5

Evidence of leaky gut in autoimmunity

Research associating elevated intestinal permeability with myriad diseases has exploded in recent decades. A 2019 systematic review, an unbiased amalgamation of research studies considered the highest grade of evidence, found that autoimmune diseases correlated with leaky gut most strongly of all conditions studied – more than gut disorders like irritable bowel syndrome.6 And it’s not just autoimmunity against the gut lining itself, such as celiac disease. Regardless of the methods used to assess the gut barrier or the autoimmune disease studied, research shows a strong connection.

Leaky gut has been identified in psoriasis since the early 1990’s.7 More recent research by a Polish team has consistently found elevated intestinal permeability in psoriasis that correlates with disease severity, using multiple indirect assessments of gut barrier function.8–10 Leaky gut is more prevalent in autoimmune hepatitis and Grave’s disease than controls, and predicts disease severity in both.11,12 Gut barrier dysfunction has been identified in Sjogren’s and systemic lupus erythematosus,13,14 and has been cited as a causative factor in type I diabetes for nearly 15 years.15,16 Intestinal permeability is significantly higher in children with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis than congenital hypothyroidism, suggesting that autoimmunity and not low thyroid function specifically correlates with leaky gut.17

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is associated with impairments to the blood brain barrier, a selective membrane that resembles and often mirrors the intestinal lining. Observational research suggests that people with MS have leaky gut, which correlates with disease activity.18 Some argue that leaky gut may be a consequence, not a cause of MS, resulting from disease-related inflammation in intestinal nerves.19 However, pharmaceutical treatment appears to improve MS without consistently reducing intestinal permeability,20,21 suggesting the gut may play an independent role. In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), leaky gut distinguishes not only those with active disease but also asymptomatic individuals with RA antibodies (“pre-RA”) from controls.22 Furthermore, greater intestinal permeability in pre-RA predicts the onset of active disease within 12 months, indicating a causative role for leaky gut.

Targeting the gut lining

What does all of this mean if you have an autoimmune disease? Emerging research emphasizes that to the extent a leaky gut contributes to autoimmunity, healing the gut may also contribute to stopping and even reversing disease. As discussed above, intestinal permeability correlates with the severity of numerous autoimmune diseases, but this is not a one-way street.

The gut microbiome, the community of trillions of organisms in our gastrointestinal tract, plays an important role in the regulation of intestinal permeability. Indeed, sterilized mice are resistant to toxin-induced autoimmune hepatitis and leaky gut, suggesting that disturbances to the healthful microbiome mediate gut barrier function and subsequent autoimmunity.23 Microbiome-targeting interventions like specific probiotics,24,25 dietary fiber,26 and bacterial byproducts such as butyrate22 alleviate animal models of autoimmune diseases. Healthy microbes also play an important role in directly regulating immune function, and modulating the microbiome may be a powerful tool for autoimmunity.3,27 Microbiota “transplants” from disease-free donors are being explored to treat MS.28

Many common food additives are toxic to the intestinal lining, including artificial emulsifiers, surfactants, solvents and nanoparticles, and researchers have hypothesized a link betweeen these additives and autoimmunity.29 Importantly, some of these byproducts of food processing do not appear on ingredient lists. Detoxification and reducing exposure to processed foods are important for autoimmunity. Sugar may be one of the strongest barrier-disrupting toxins of all, and blood glucose regulation improves intestinal permeability.30

Since psychological stress may contribute to autoimmunity, as well as directly disturb the intestinal barrier,31 mental-emotional therapies may help heal autoimmunity on a physical level. Inflammation from any cause can itself trigger leaky gut, which can continue to fuel inflammation in a vicious cycle. Functional medicine has an arsenal of tools to calm this process and restore the gut, including herbs, micronutrients, and probiotics, helping to heal autoimmunity from the inside out.

Talk to a functional medicine doctor about how addressing your gut health might be the missing piece to finding more lasting health with autoimmunity.

References:

- Lerner A, Jeremias P, Matthias T. The World Incidence and Prevalence of Autoimmune Diseases is Increasing. Int J Celiac Dis. 2015;3(4):151-155. doi:10.12691/ijcd-3-4-8. http://pubs.sciepub.com/ijcd/3/4/8/index.html

- Wang W, Zhou H, Liu L. Side effects of methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;158:502-516. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.027. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0223523418307992

- Mu Q, Kirby J, Reilly CM, Luo XM. Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:598. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28588585/

- Vojdani A. Molecular mimicry as a mechanism for food immune reactivities and autoimmunity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2015;21 Suppl 1:34-45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25599184/

- An J, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. The Role of Intestinal Mucosal Barrier in Autoimmune Disease: A Potential Target. Front Immunol. 2022;13:871713. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.871713. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35844539/

- Leech B, Schloss J, Steel A. Association between increased intestinal permeability and disease: A systematic review. Adv Integr Med. 2019;6(1):23-34. doi:10.1016/j.aimed.2018.08.003. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221295881730160X

- Humbert P, Bidet A, Treffel P, Drobacheff C, Agache P. Intestinal permeability in patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci. 1991;2(4):324-326. doi:10.1016/0923-1811(91)90057-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1911568/

- Sikora M, Chrabąszcz M, Maciejewski C, et al. Intestinal barrier integrity in patients with plaque psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2018;45(12):1468-1470. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14647. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30222202/

- Sikora M, Stec A, Chrabaszcz M, et al. Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein, a Biomarker of Intestinal Barrier, is Associated with Severity of Psoriasis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(7):E1021. doi:10.3390/jcm8071021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31336842/

- Sikora M, Chrabąszcz M, Waśkiel-Burnat A, Rakowska A, Olszewska M, Rudnicka L. Claudin-3 – a new intestinal integrity marker in patients with psoriasis: association with disease severity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 2019;33(10):1907-1912. doi:10.1111/jdv.15700. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31120609/

- Lin R, Zhou L, Zhang J, Wang B. Abnormal intestinal permeability and microbiota in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(5):5153-5160. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26191211/

- Zheng D, Liao H, Chen S, et al. Elevated Levels of Circulating Biomarkers Related to Leaky Gut Syndrome and Bacterial Translocation Are Associated With Graves’ Disease. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:796212. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.796212. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34975767/

- Gudi R, Kamen D, Vasu C. Fecal immunoglobulin A (IgA) and its subclasses in systemic lupus erythematosus patients are nuclear antigen reactive and this feature correlates with gut permeability marker levels. Clin Immunol Orlando Fla. 2022;242:109107. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2022.109107. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36049603/

- Sjöström B, Bredberg A, Mandl T, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and multiple sclerosis. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4:100082. doi:10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100082. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33506194/

- Mønsted MØ, Falck ND, Pedersen K, Buschard K, Holm LJ, Haupt-Jorgensen M. Intestinal permeability in type 1 diabetes: An updated comprehensive overview. J Autoimmun. 2021;122:102674. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102674. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34182210/

- Vaarala O, Atkinson MA, Neu J. The “perfect storm” for type 1 diabetes: the complex interplay between intestinal microbiota, gut permeability, and mucosal immunity. Diabetes. 2008;57(10):2555-2562. doi:10.2337/db08-0331. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18820210/

- Küçükemre Aydın B, Yıldız M, Akgün A, Topal N, Adal E, Önal H. Children with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Have Increased Intestinal Permeability: Results of a Pilot Study. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2020;12(3):303-307. doi:10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2020.2019.0186. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31990165/

- Camara-Lemarroy CR, Silva C, Greenfield J, Liu WQ, Metz LM, Yong VW. Biomarkers of intestinal barrier function in multiple sclerosis are associated with disease activity. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl. 2020;26(11):1340-1350. doi:10.1177/1352458519863133. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31317818/

- Parodi B, Kerlero de Rosbo N. The Gut-Brain Axis in Multiple Sclerosis. Is Its Dysfunction a Pathological Trigger or a Consequence of the Disease? Front Immunol. 2021;12:718220. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.718220. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34621267/

- Olsson A, Gustavsen S, Langkilde AR, et al. Circulating levels of tight junction proteins in multiple sclerosis: Association with inflammation and disease activity before and after disease modifying therapy. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;54:103136. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2021.103136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34247104/

- Buscarinu MC, Gargano F, Lionetto L, et al. Intestinal Permeability and Circulating CD161+CCR6+CD8+T Cells in Patients With Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Treated With Dimethylfumarate. Front Neurol. 2021;12:683398. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.683398. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34512507/

- Tajik N, Frech M, Schulz O, et al. Targeting zonulin and intestinal epithelial barrier function to prevent onset of arthritis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1995. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15831-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7181728/

- Cai W, Ran Y, Li Y, Wang B, Zhou L. Intestinal microbiome and permeability in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31(6):669-673. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2017.09.013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29566910/

- Secher T, Kassem S, Benamar M, et al. Oral Administration of the Probiotic Strain Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 Reduces Susceptibility to Neuroinflammation and Repairs Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis-Induced Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1096. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01096. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28959254/

- Liu Q, Tian H, Kang Y, et al. Probiotics alleviate autoimmune hepatitis in mice through modulation of gut microbiota and intestinal permeability. J Nutr Biochem. 2021;98:108863. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2021.108863. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34517094/

- Hu ED, Chen DZ, Wu JL, et al. High fiber dietary and sodium butyrate attenuate experimental autoimmune hepatitis through regulation of immune regulatory cells and intestinal barrier. Cell Immunol. 2018;328:24-32. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.03.003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29627063/

- Kinashi Y, Hase K. Partners in Leaky Gut Syndrome: Intestinal Dysbiosis and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2021;12:673708. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.673708. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33968085/

- Al KF, Craven LJ, Gibbons S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation is safe and tolerable in patients with multiple sclerosis: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Mult Scler J – Exp Transl Clin. 2022;8(2):20552173221086664. doi:10.1177/20552173221086662. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35571974/

- Lerner A, Matthias T. Changes in intestinal tight junction permeability associated with industrial food additives explain the rising incidence of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(6):479-489. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.009. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25676324/

- Thaiss CA, Levy M, Grosheva I, et al. Hyperglycemia drives intestinal barrier dysfunction and risk for enteric infection. Science. 2018;359(6382):1376-1383. doi:10.1126/science.aar3318. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29519916/

- Ilchmann-Diounou H, Menard S. Psychological Stress, Intestinal Barrier Dysfunctions, and Autoimmune Disorders: An Overview. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1823. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01823. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32983091/